Booktext, June 07--The Third Policeman

June 2007

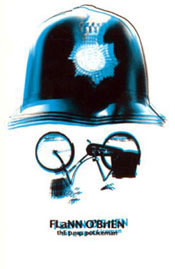

Spotlight: The Third Policeman

Author: Flann O'Brien

Year: 1967

Length: 200 pages (appx.)

Publisher: Dalkey Archive

The Third Policeman is, strictly speaking, a confession on the part of our narrator, and it's very easy, for a significant portion of the book, to expect that it doesn't really go any deeper than that.

The Third Policeman is, strictly speaking, a confession on the part of our narrator, and it's very easy, for a significant portion of the book, to expect that it doesn't really go any deeper than that.

The narrator (wisely unnamed) and his closest friend (or, I should say, the closest thing he has to a friend) decide to murder an old man, bury the body, and abscond with his finance box. We are told--with pleasingly gory detail--about the crime itself, which, excepting some brief explanation, opens the novel with one hell of a bang. (Ahem...)

We don't detect any real regret on the part of narrator (and absolutely none on the part of his friend John Divney) and the novel reads like an apology that contains all of the facts but none of the emotion, and there is nothing to convince us that this is unfolding in any world other than our own until the narrator breaks into the house of the murdered man to retrieve the money and finds...well, the murdered man, sitting in a chair, perfectly capable of carrying on a conversation with his killer, so long as nobody minds that he can only answer questions in the negative.

And this is where the book really picks up, and where O'Brien begins writing at his best. (Not just "his best" for the purposes of this book...I'm taking into account his entire career.) The narrative takes a gorgeous turn for the surreal as the narrator continues on an increasingly bizarre path through the town he thought he knew, meeting all manner of derranged, horrifying individuals--not the least of which are the three mad, monsterous police officers he enlists to help him find the money.

The Third Policeman is an amazingly accomplished book considering how little experience O'Brien had with the surreal. It's equal parts Through the Looking Glass and The Hitch-hiker's Guide to the Galaxy. Every few pages our narrator finds himself enmeshed in some impossible situation or absurd conversation and they unfold like a series of fables, each on the back of the other, in such a delightful way that you might have to keep reminding yourself of the horrifying main plot upon which these beautiful moments perch.

It's all too easy to construct a list of the novel's best features (a band of one-legged vigilantes, a series of chests decreasing in size unto infinity, men who turn into bicycles so gradually most people don't even notice...) but that almost makes it sound like a checklist of the absurd, and it robs O'Brien of his masterful storytelling...and, let's face it, some of the most clever dialogue ever set to print.

What's most interesting about this novel to me, though, is that O'Brien was so displeased with it that he pretended to have lost the manuscript. It was not published until after he died. If ever one needed evidence that the artist is the person least-equipped to make qualitative judgments of his own work, The Third Policeman is as far as anyone needs to look.

Why he was displeased with the story is anyone's guess...I'm not sure there is any conclusive answer--at least not one we can reach without input from the man himself. (And, as he's dead, he'd only be able to answer in the negative...) A good deal of this book was later reworked for his novel The Dalkey Archive, but that book was so limp and aimless that one must (must!) wonder how he ever found it superior to The Third Policeman in any sense.

This is by quite a wide spread his best novel, beating even the brilliant At Swim-Two-Birds without contest. It's impossible to know what O'Brien had in mind when he started writing The Third Policeman, but the fact that a novel this good, this well-structured, this deep and endlessly re-readable fell so short of it to seem disgraceful to the man proves that he had a mind very far ahead of his time.

We'll never know what The Third Policeman "should have been." We'll only know what it is: one of the finest examples of Irish literature, period.

![]()

Papercuts:

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, Michael Chabon (2000, 640 pages, appx.)

Thank Christ I read this book directly after The Time Traveler's Wife. Had I chosen something less recent I might have just been able to convince myself that I never wanted to read living authors again. This is the story of two young cousins who come together not only to create the next big comic book character, but they use him to fight a subversive, indirect war against Nazi Germany.

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay is an absolutely brilliant read...though the quality of the writing outruns the quality of the story and characters by quite a bit. Not a damning criticism by any means, but there's a lot that I would have liked to see hammered out. The character of Rosa Saks, in particular, never ceased to irritate me with her presence. She functioned just fine as an object of desire for the two cousins, but as a character you need to spend time in a room with...well...you do kind of have to wonder what anybody saw in her. Which I don't think was Chabon's aim...

Basically the story petered out once the cousins lost interest in their own creation...which is appropriate, I have to admit, but that doesn't stop the novel from feeling about one hundred pages too long. That said, I would recommend it, because there are some truly engrossing passages in that book, and Sammy Clay could possibly be one of my favorite characters from recent literature.

![]()

The Crying of Lot 49, Thomas Pynchon (1965, 150 pages, appx.)

I think, by now, I may have read this novel more times than any other. (The "I think" comes from the many, many readings I've given Catch-22 over the years.) But every time I read through it I find some new connection between events, some new parallel in the dialogue, some absolutely hilarious hidden word-gag that I kick myself for having missed so many times before.

The Crying of Lot 49 is an easy re-read because of its brevity. (I recommend you read it at least once in a single sitting...it gives you one hell of a powerful bird's-eye view of the characters and will help you draw many of the connections you'd otherwise miss.) It stands as a testament to the fact that, if only life were longer, endless re-readings of Pynchon can be probably the most rewarding thing about modern fiction. His novels are alive...they layer themselves long after he's stopped writing them.

This time around, for those keeping score, I was able to see the connection between an aerosol spray can that whizzes past Oedipa's ear in a motel room and a bullet fired at her by her psychiatrist (Dr. Hilarius) that whizzes past her ear toward the end of the novel. It was a rewarding find. I gave myself a kiss.

![]()

To the Lighthouse, Virginia Woolf (1927, 210 pages, appx.)

It sure was a good month of reading, I have to say. At the recommendation of a new friend of mine I picked up To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf and found the first novel written by a woman that didn't completely annoy me.

In fact, it's actually rather great, and I already owe it at least two or three more re-reads. The first section is charmingly deceptive...what seems to be a quiet exploration of familial interaction accellerates at an absolutely horrifying rate in the second section so that by the time you get to the third you feel as though you've been through a war...and perhaps not successfully.

She uses the simplicity of her setting to her advantage and manages to creatively catch the reader off guard with the unpredictable significance of minor details. Lovely stuff.

![]()

your commentary is accurate and pleasing in most respects, but neglects to mention the sheer poetry of O'Brien's writing - his descriptive passages are a joy. Although dystopian the hell our narrator is wandering through is tranquil and beautiful. and the novel includes the definitive sentence on hens.

Joe d

By Joe Dugdale

April 03, 2008 @ 9:29 pm

reply / #